Emigrating e-Services: Diasporic insta-advocacy and the Egyptian ID card renewal process

By Nadine Loza

Picture by the author

In September 2020 the Egypt Diaspora Initiative (EDI) successfully campaigned to establish the Egyptian national identity (ID) card renewal as a permanent consular service worldwide amid the growing need for countries to expand, export or ‘emigrate’ remote and electronic public services (ePS) to their citizens abroad.

Housed on social media platform Instagram, the EDI is an independent and inclusive virtual gathering of over 50,000 Egyptian migrants globally. It has served as a source of news, forum for debate, network of support and catalyst for change since 2017, addressing both conceptual and practical issues affecting Egypt’s diaspora.

Of all the enquiries received by the EDI, those concerning ID cards are among the most recurrent. Necessary for passport issuance, electoral participation, property registration, banking transactions and just about every administrative scenario linked to Egypt, a valid ID card is the fundamental tool and token of citizenship.

Prior to the pandemic, renewing an Egyptian ID card overseas was challenging and time-consuming. It entailed contacting the nearest consulate to express interest in the service and then waiting for a minimum of 500 such requests to accumulate, at which point a committee from Egypt’s Civil Status Department would visit to process applications with card delivery expected eight weeks later. Contrastingly, Egyptians in Egypt are able to submit a renewal request any time – either in person, via a hotline or the official ePS portal – and have their new ID card ready in as little as twenty-four hours.

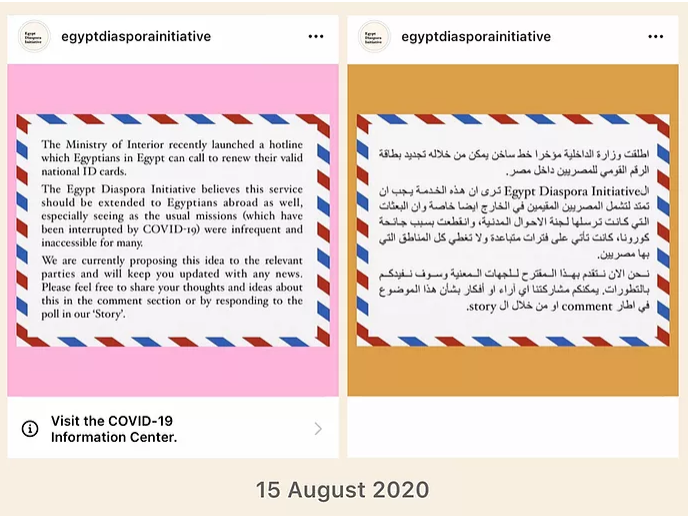

When COVID-19 mobility restrictions led to a full and indefinite suspension of the ID missions sent abroad, demand for ID cards not only persisted but multiplied as emigrants who may have otherwise applied during trips back to Egypt postponed their travel plans. Noting this intensifying problem, in August 2020 the EDI proposed the idea of a consular hotline or portal to policy-makers and conducted an online poll wherein 90% of respondents agreed that non-resident nationals should be offered an alternative renewal method.

Figure 1. Screenshot of EDI post

Our efforts to find a solution proved fruitful: Egyptians abroad were soon granted the right to renew their ID cards at Egyptian embassies and consulates directly, all year round. This promising stride has enabled those living further away from these sites to journey there when it suits them instead of being rushed and restricted by the brief window of access when a committee would be present. Eliminating the element of time pressure and streamlining the process so that it can now partially be completed by mail have helped in maintaining physical-distancing measures as the chance of queues or crowding is minimised.

The pandemic has revealed the urgency of boosting consular crisis preparedness through investments in digitisation and digitalisation approaches; but even extraneous to an emergency, the speed of the digital era itself requires faster consular reaction cycles. Introducing more flexible, remote and virtual options based on agile, scalable, human-centred technology will allow for service delivery that is responsive to changing situations and evolving demands.

Digitisation could further improve consular services by increasing efficiency and reducing costs. While in Egypt there are three price points for ID card renewal depending on processing speed and starting at the equivalent of USD 2, Egyptians abroad must pay a set fee of approximately USD 100.

The possibility of delivering consular services electronically is still being explored because there are a number of factors to consider, namely authentication and the development of a secure digital infrastructure. To mirror the innovative and convenient variety of Egypt’s award-winning internal public service delivery system, any future ePS projects aimed at the diaspora will also need to be complemented by analogue options.

Figure 2. Screenshot of EDI post.

Article 36 of the 1963 Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, to which Egypt acceded in 1965, focuses on communication between sending states and their nationals with a view to facilitating the exercise of consular functions.

Carried into the contemporary context, this means strengthening feedback flows, co-designing policies and continually refining ePS systems based on reviews. A central concern is that consular services do not have an intuitive and evidence-based understanding of how citizens respond to different kinds of services so unquantifiable experiences and opinions should be taken into account along with statistics and data. Involving the main stakeholders early on will help ensure digitisation projects are viewed from the citizen’s perspective and not merely as a modernisation scheme.

Launching ePS for emigrants is useful in terms of speed, cost and communication, but may not always be the best service delivery option. A transparent and ongoing multi-stakeholder, multi-channel, multilateral conversation and comparison of best practices will help all consulates adapt long-term.

Nadine Loza

Nadine Loza is Founding Director of the Egypt Diaspora Initiative, which aims to raise issues of interest to Egyptians living abroad and voice their concerns; establish a close link between Egyptian communities all over the world and in Egypt, cutting across political and religious affiliation, age and gender, and free of commercial interests; and strengthen solidarity with Egypt among Egyptians in the diaspora.

You can reach the EDI by email at egyptdiasporainitiative@gmail.com or on Instagram @egyptdiasporainitiative.

This article is part of the issue ‘Empowering global diasporas in the digital era’, a collaboration between Routed Magazine and iDiaspora. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) or Routed Magazine.